Briefing Room

Overview

The 1st Battalion Cambridgeshires, ‘The Fen Tigers’, had landed in Singapore on the 29th January 1942 and were met by the senior officers of the 18th Division who told them bluntly that they were too late. Malaya was lost, Singapore was next and there was no escape. There was to be no ‘Dunkirk’ here. The Battalion CO, Lieutenant Colonel Gerald Goodwin Carpenter advised his officers not to tell the men.

The Cambridgeshires had spent two months getting to Singapore. They were met off the gangway with the news that Singapore was expected to fall.

Singapore was burning. Bombed constantly for two months and soon to be cut off from Johor, the island was officially under siege. Over 90,000 allied troops had been shoe-horned into the islands defences in preparation for the expected Japanese attack and the Cambridgeshires were part of the last boatload in. The battalion was sent to defend Seletar Airfield in the north of the island, where the last vestiges of the Royal Air Force were starting to pack up and head out. Here the Cambridgeshires remained dug in for a week at the end of which news filtered through that the Japanese had landed in the west and had broken through the fragile Australian lines. The invasion had started and the Cambridgeshires were in the wrong place, facing the wrong way and about to be outflanked.

On the evening of the 10th February orders arrived for the battalion to move west to set up a defensive ‘stop line’ along the Adam Road. However a third of the battalion (B & C Coys) was to go on patrol in the jungle and plantations to the north of MacRitchie Reservoir and actively stop any enemy incursions towards the strategic pumping stations at Thompson Village that supplied fresh water to the city. The remaining Cambridgeshires were driven down to Adam Road arriving on the 12th February.

The Cambridgeshires were asked to defend a line almost a mile long with the southern shores of MacRitchie reservoir on their right and the Adam Park Estate on their left. A Company was strung out in positions on Hill 95 overlooking the pristine fairways of the Singapore Island Country Club Golf Course in the centre of the line and on Water Tower Hill slightly further to the West. D Company had the simple task of fortifying and defending the housing estate.

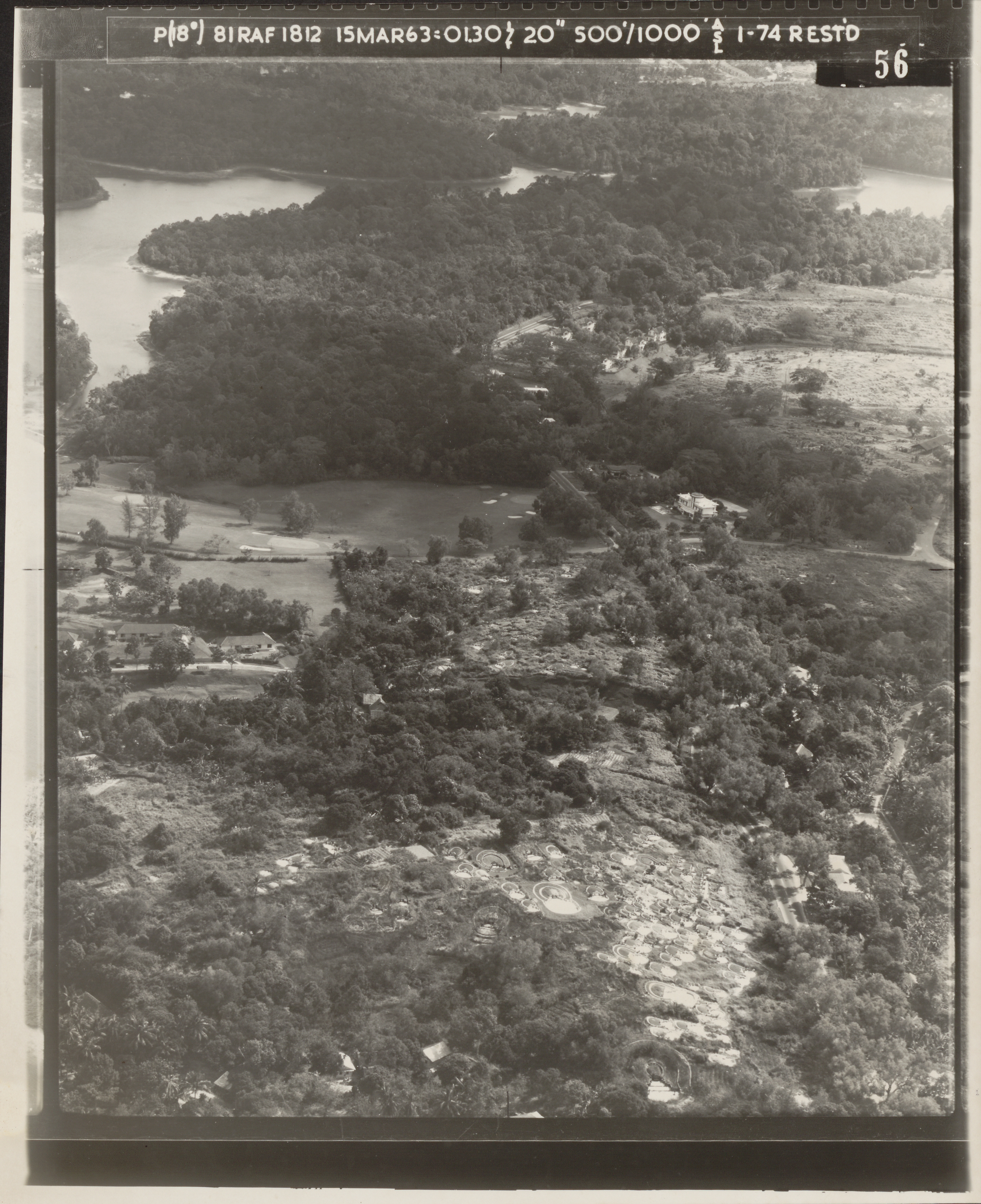

Hellfire Corner (middle), Hill 95 (foreground)and the end of the SICC Golf course became the centre of the Cambridgeshire’s defensive position on the evening of 13th February (image courtesy National Archives of Singapore)

Hellfire Corner (middle), Hill 95 (foreground)and the end of the SICC Golf course became the centre of the Cambridgeshire’s defensive position on the evening of 13th February (image courtesy National Archives of Singapore)

Captain Hockey and his men along with the battalion’s Pioneer Company set about digging trenches in the gardens, fortifying the houses and laying barbed wire along the foot of the small valley that lay between them and A Company positions to the north.

The sound of battle built up throughout the day and fleeing allied troops filtered through the lines. What they reported was not good. Tomforce, the only concerted counterattack to be launched by the Allies had been easily beaten back and now there was nothing between the Cambridgeshires and the advancing Japanese troops of Yamashita’s crack 5th Division. By the evening of the 12th February the enemy artillery fire began to pepper Water Tower Hill and the immaculate fairways of the golf course. Japanese aircraft flew lazily along the line of the Lornie and Adam roads without much of a care, frustratingly out of the reach of the Cambridgeshires AA fire and confident the RAF had left town.

Friday 13thFebruary dawned brightly and stifling hot. D Company stood to before dawn and watched in stunned amazement as 9 Platoon, A Company, on Water Tower Hill was simply overwhelmed by a wave of Japanese troops from the 41st Regiment (Fukuyama). By late morning the position on the adjoining hills was getting desperate with the remains of A Coy pinned down in their trenches at the foot of Hill 95. Carpenter could not afford to let the Water Tower Hill go without a fight so he despatched Captain Dan Marriott’s Reinforcement Company into the estate from where they could launch an attack across the valley and up the grass covered slopes of Water Tower Hill. Captain Hockey’s ‘D’ Company provided covering fire. Three times the Reinforcement Company attacked the Japanese positions each time edging a little closer to the now demolished water tank on its summit. Finally by mid afternoon they reported the hill cleared of enemy troops but at great cost. Most of the officers, including Marriott, and SNCO’s had been killed or wounded and the company was effectively wiped out. But they had given Carpenter time to strengthen his defences. A Company had regrouped on Hill 95 and B and C companies had finally joined them having returned from their overnight jungle patrol.

As darkness fell across the estate, news came that the Cambridgeshires were to be relieved on Hill 95 by the battered yet defiant 4th Suffolks. These men had already taken part in the Tomforce fiasco and had regrouped behind Adam Road. Now they were brought up onto Hill 95 and relieved A, B and C Company. Carpenter decided to move C Company into the estate and the remaining men took up positions on the eastern side of Adam Road in a deserted RASC camp.

In the early hours on the morning C Company made its way into the housing estate taking over positions vacated by D Company. In doing so however they left a number of houses vacant and by dawn on the 14th February the Japanese had moved men into the empty accommodation. C Company positions in No.19 Adam Park at once came under fire from enemy machine gunners in No20 next door, a range of no more than 50 yds. The Cambridgeshires set about dislodging the new threat by launching bombing attacks under the cover of small arms fire. Several patrols made it as far as the main buildings but by 1100 and with casualties mounting up the house remained in enemy hands. 2nd Lt Clift, OC 13 Platoon, then organised a ‘mixed blitz’ in which Boys AT rifles and 2” mortars, fired horizontally, were used to blast holes in the wall and then followed up by hand grenades and Thompson SMG fire. 2nd Lt Fulcher and two sections from 14 Platoon managed to clear two adjacent buildings before being forced back under heavy machine gun fire.

No. 20 Adam Park became the scene of a ferocious house clearing operation on the morning of the 14th February as IJA forces breached the estate perimeter.

No. 20 Adam Park became the scene of a ferocious house clearing operation on the morning of the 14th February as IJA forces breached the estate perimeter.

As the day wore on the Japanese launched an attack across the valley to retake the lost houses. They were met by a hail of fire from the entrenched positions in the gardens of the Adam Park bungalows that stopped them in their tracks. Pressure was also mounting to the south of the estate as the 1/5th Foresters held their ground along Adam Road with supporting mortar fire from the Cambridgeshire 3” Mortar teams. Japanese shelling and mortaring was persistent but ineffective, sometimes the situation being compounded by allied shells falling short. By early evening the bombardment reached a crescendo but the Cambridgeshires held firm in their slit trenches. To the north however the situation was different. The bombardment here had been the prelude to a massive assault by the IJA’s 11th Regiment accompanied by tanks that smashed through the beleaguered 4th Suffolks. An assault by 40 to 50 Japanese on the northern perimeter of the estate was once again beaten back by combined small arms and mortar fire; however the loss of Hill 95 meant that Carpenter’s right flank had been turned.

That evening Carpenter rose defiantly from his slit trench and bellowed ‘All Cambridgeshire positions are in Cambridgeshire hands’ – a cheer cascaded around the estate as the news was passed on.

The night of the 14th / 15th February passed by relatively quietly, the shelling was less intense, the sniping less of a threat and the patrols less traumatic.

It was clear to Carpenter however that the ‘stop line’ to the north had collapsed as his forward observation points maintained a steady stream of reports of Japanese troops and tanks heading east along the Sime Road. He summoned his officers to a morning briefing in the front garden of No.17 and was just about to ask their advice when a line of machine gun bullets tore up the ground between them and sent the group scrambling for cover. Clearly the Japanese were in possession of Hill 95 and now way behind the Cambridgeshires right flank. Somewhat peeved by his narrow escape, Carpenter ordered Captain Spooner, OC 3 Platoon (Mortars) to have his men lob a few shells in the direction of the golf course in retaliation. Sgt Holyhead duly obliged sending 60 rounds over the hill. Not that they knew it at the time but this speculative shooting landed on a company of tanks who believing themselves safe had left their hatches open. Six tanks were reportedly destroyed.

Things were now to get worse for the beleaguered Cambridgeshires. 1/5 Foresters were about to withdrawal from their positions along Adam Road to the south. A number of pleas to stay were sent but by midday it appeared the Foresters had vacated their positions. On top of this the Japanese gunners had honed in on A and B Company dug in around the RAOC hutted encampment on the eastern side of Adam Road, setting the parched grass on fire and forcing some of the men to abandon their slit trenches. Rounds also fell on Spooner’s 3” mortar sections as they were redeploying to the area, killing and wounding many of the teams and destroying their ammunition stocks. In one barrage the Cambridgeshires most potent attacking weapon had been wiped out.

7 Adam Park was used by Lt Col Carpenter as his Battalion HQ.

7 Adam Park was used by Lt Col Carpenter as his Battalion HQ.

Carpenter, now commanding from the ‘cellar’ underneath 7 Adam Park, realised their time was up and at 3.30 on the 15th February he called his Brigade HQ requesting permission to withdraw his men. In anticipation of consent he ordered the remaining elements of A and B Company to make a mad dash across Adam Road and take up positions around the HQ prior to forcing a break out south, along Adam Road to the junction of Farrer and Bukit Timah. The reply Carpenter received was not what he had expected. The Cambridgeshires were to stay exactly where they were…. and lay down their arms. General Arthur Percival was surrendering Singapore.

It took some time for the word to get around the estate of the surrender and for the message to sink in. Firing continued sporadically for the next hour. Around 5.00 a Bren gun fired upon Japanese troops collecting their wounded on Hill 95 and in retaliation their tanks and small arms opened up on No.17 Adam Park which housed the Cambridgeshire’s Regimental Aid Post (RAP) setting it alight. One orderly was killed but the wounded were safely evacuated into the back garden. The valuable medical supplies however were lost.

Finally the firing fell away and Carpenter walked out onto Adam Road to negotiate the surrender of his men. The officers and wounded were separated out and quartered in the wreckage of the houses. Around five hundred OR’s were herded into a tennis court where they were to remain with little food or water and no sanitation for 4 more days. On the 19th February, a week after having arrived, the Cambridgeshires marched out of Adam Park for the last time and headed into 3 1/2 years of brutal captivity starting with a route march to the notorious Changi Prison.

The 1st battalion Cambridgeshires left Adam Park on the 19th February 1942 bound for imprisonment at Changi and they were not to return to the estate. However two months after the surrender, the Japanese, somewhat overwhelmed by the number of Allied prisoners they had taken, decided on dispersing their captives to various work camps around the island in an attempt to clean up the damage the fighting had caused. They also tasked 10,000 men to the building of a Shinto Shrine to honour the Japanese war dead on the banks of the MacRitchie Reservoir.

2,000 Australians were first of the Shrine workforce to arrive at Adam Park on 3rd April 1942. They were ordered to make best use of the bombed out buildings for their accommodation. What they found was an appalling mess. The houses had been left to rot. The roofs and walls were perforated by the fall of mortars and shells and the rooms infested with mosquitoes. Bodies of soldiers and civilians lay unburied around the grounds. The drainage and sanitation were smashed up and the electricity had been cut. The houses had been looted and left devoid of usable furniture. For many of the POWs the first night was spent on the concrete floors of the outhouses with little more than what they carried to provide succour. In the morning the roll call was taken and the first of the daily work parties was marched out onto the SICC Golf Course to start the process of building access roads to the new shrine.

Lt Col Roland Oakes was the camp commander at Adam Park

Lt Col Roland Oakes was the camp commander at Adam Park

Lt Colonel Roland Oakes, formerly the commanding officer of 2/26 battalion, was in overall command of the detachment and he was given a surprisingly free rein to set up the camp. Providing the required numbers of troops were available each morning for the work parties the Japanese commanders paid little attention as to what went on in the camp. Oakes and his staff set about establishing a fully functioning military barracks within the wreckage of the estate. All the facilities one might expect in a camp back home were set up. The men were billeted in the houses around the periphery of the estate keeping as much as they could within their battalion structure with about 250 men in each house. They were to be found in every room, some even preferring to live under the bungalows or in the outhouses, garages and maids quarters. The external kitchens at the back of each house were used for making the food and latrines were dug in the gardens. A few weeks after their arrival the men of 8th Division Signals used their familiarity with wiring to get the electricity working and the men of the 2/5th Hygiene section restored the sanitation and running water. The Australians were very adept at scrounging and soon a treasure house of broken fittings and fixtures had been ‘acquired’ to provide a selection of improvised furniture.

Somewhat belatedly, a thousand British troops arrived the following month under the command of Lt. Col. Madden R.A, including men from the Gordon Highlanders under Major Reginald Lees and the Leicestershires and the East Surrey men from the ‘British Battalion’. With most of the best accommodation now firmly allocated to the AIF they found themselves relegated to the six abandoned houses in the neighboring Watten Estate.

Oakes brought in a surgical team led by Major Hugh Rayson of the 2/10 Field Ambulance who set up a hospital which remarkably included a laboratory to analyse various samples brought in from the local camps and a fully functioning dental surgery. The officers not assigned to command of the accommodation buildings were housed in what became known as the ‘Captain’s House’ and Oakes even established an orderly room and somewhat ironically a ‘prison’. Other houses were converted into a canteen (set up by the Japanese and manned by local Chinese to encourage official trading), a chapel housed in the upper floor of a bombed out house above the canteen and a theatre, The Tivoli, which boasted in its heyday an orchestra of over 60 musicians performing on a stage built into a double garage. The Japanese took over another house as their guard room but there were few guards around place. By mid way through the stay the prisoners were asked to guard themselves, having to post sentries at various points with the remit to limit movement around the camp. In fact for the first few months there was little to stop prisoners walking down to town to trade what little items and money they had. A barbed wire perimeter fence was not installed until May 1942.

The ruined remains of No.11 Adam Park was used by the POWs for a Chapel and Canteen (Courtesy of BHFineart)

The ruined remains of No.11 Adam Park was used by the POWs for a Chapel and Canteen (Courtesy of BHFineart)

Work was regular and tedious, the pace slow and laboured as both Japanese and allied troops worked hard to get just enough done to keep their senior offices happy. Beatings were common though and the deaths of a number of men could be put down to the after effects of serious punishment however on the whole the relationship between captors and captives was one of working to the mutual benefit of the other.

The biggest killer proved to be the poor diet and tropical climate. Men in the camp were initially given a daily rice ration of 22oz which was quite substantial yet lacked essential vitamins. The doctors worked tirelessly combating diseases brought on by lack of a balanced diet and trying to obtain other sources of valuable vitamins and anti- malarial drugs. The medical staff arranged for diverse excursions in search of food supplements; polished rice was brought in from the mills in Johor and malt and yeast obtained from various visits to the local Tiger Beer breweries. However men still fell ill and although only eight were reported as having died at Adam Park and buried in the camp cemetery, many more were moved back to Changi with life threatening illnesses.

By October 1942 the shrine had been finished and the men were not required to work as hard. For a few weeks boredom was the main worry. An inter battalion 7-aside Rugby League competition proved popular, being played on the tennis courts in the centre of the estate and book clubs, lectures and guest’s nights were also encouraged. However in late October the first party of 650 British were taken out of the camp and sent to Thailand, another 80 followed the next day. The remaining AIF were moved that November into the recently vacated accommodation in the Sime Road Camp or moved back to Changi. They too were destined to eventually leave for the Railway, the work camps in Borneo or the factories in Japan. Soon the relatively comfortable existence in Adam Park was all but forgotten and a new hell prevailed.

Australian POWs worked on the Shinto Shrine and the ceremonial bridge in 1942. (Courtesy of AWM)

Australian POWs worked on the Shinto Shrine and the ceremonial bridge in 1942. (Courtesy of AWM)

Adam Park was not totally stripped of prisoners however. The majority of the houses were rebuilt and re-let for the duration of the war to the Japanese hierarchy and Sime Road internees were brought in to help tend the gardens. In 1945 Allied forces in Singapore to organise the surrender of the Japanese found Australian, Dutch and British prisoners at the Adam Road camp, a collection of huts in the old RAOC camp opposite Adam Park. These men were the survivors of the Railway who had been brought back to Singapore to help prepare the islands defences for the impending allied invasion. These ‘Tunnelling Parties’ were responsible for the construction of miles of underground labyrinths that honeycombed the centre of the island.

Adam Park has an incredible wartime heritage. There is no other place quite like it in Singapore or probably SE Asia. The fact that it is the scene of three days of intense fighting and a POW work camp and it is still remarkably intact makes Adam Park a unique window into Singapore’s WW2 past.

The history of Adam Park tells of a remarkable story of wartime resilience.